Anthology of texts

22-Falangola.pdf

Documento Adobe Acrobat [100.5 KB]

1961. Time of "Continuità"

by Flaminio Gualdoni

(from the exhibition's catalogue: 1961. Tempo di continuità, Milan, Fondazione Arnaldo Pomodoro, curated by F. Gualdoni, F. Giani, settembre – dicembre 2014, pp. 76-82)

In February 1961 the Odyssia gallery in Rome presented the exhibition called "Consagra, Dorazio, Novelli, Perilli, Turcato", dedicated to what the prefacer Giulio Carlo Argan indicated as "the

continuum". He theorised that the "opposite of representation or form, understood as catharsis, is not the fragment, but is the continuum: in fact form is limit, the continuum is absence, uncertainty

of the limit".

A common and evident characteristic for all the five artists was that they practice non-objective art, and having passed the maturation phase now live their stable, recognisable and more than

substantial artistic identity to the full.

Four arose from the fervid pioneering season of "Forma" the single issue journal that on the 15 April 1947, in the heat of the arguments over the relationship between art and political militancy (the

Lettera a Togliatti in "Il Politecnico", in which Elio Vittorini denied that you have to "blow the whistle for the revolution", came out a month before), robustly sustained that "we who claim to be

Formalists and Marxists, are convinced that the terms Formalism and Marxism are not irreconcilable, especially today when the revolutionary elements of our society have to maintain a revolutionary

and avant-garde position".

Gastone Novelli was never part of that experience (he only returned from his Brazilian stay in 1949), but he is the principal interlocutor of Achille Perilli from the time of the journal-laboratory

"L'Esperienza Moderna", whose first number came out in 1957, one of the primary references of the generational segment which actively worked to overcome the informal culture in a finally cosmopolitan

key, no longer prisoner of the sterile polarity between abstraction and realism. Perelli wrote there about the "new figuration" (his Nuova figurazione per la pittura came out in number 1) in a

totally anti-realist sense, imagining a space of abstract form and tale, but with an intimate organicity: whose ethical measure is, the artist writes, in "wanting to concentrate in a precise,

concrete, real image the uncertainties, the imbalances, the irrational fears that has spread throughout our civil world". In such a way, among the references, apart from the same Novelli, there are,

as the "L'Esperienza Moderna" documents, Cy Twombly, Toti Scialoja, Antonio Corpora, Arnaldo and Gio' Pomodoro, Karl Otto Götz, Camille Bryen, amongst others.

Argan's text is very clear from certain points of view. He does not identify a group but a problem area, which clearly contrasts with both the unquestioning beliefs of concretism of M.A.C. and

around, as well as the breaking onto the scene of evolved forms of realism, updated through the example of Arshile Gorky and on the suggestions of the French nouveau roman, for which you should go

spending the definition of "existential realism".

The group, in fact, did not start through the scholar's initiative but from a recognition by the artists themselves, especially in the certainty of what they did not want to be, and the awareness

that the end of that decade had been extraordinary, but the vortex of the novelty, the arguments, the proliferation of groups and theories, risked to overwhelm positions that may have been

intellectually more lucid but less easy to turn into slogans to use.

After all, it was since 1958-1959, that a mixed group of artists, all, for different reasons, strongly argumentative about the latest and re-theorising outcomes of the informal, had aimed at

outlining its own recognisable ubi consistam within the irruption of the new.

The Pomodoro brothers and Franco Bemporad were working in Milan, already attracted to the openly post-informal orbit of the Contro lo stile manifesto of September 1957, and very present in the

network of relations that were kept in journals such as "Gesto", "L'Esperienza Moderna", "Direzioni", "Azimuth", "Metro", just to remain in Italy.

Bemporad had just returned from his 1958 one-man show at Iris Clert in Paris and in 1960 he was present at the Milione, Milan, introduced by Franco Russoli and Michel Tapié. Gio' Pomodoro in 1959

presented Fluidità contrapposta at "Documenta 2", Kassel, and won a prize at the "1ère Biennale de Paris. Manifestation biennale et internationale des Jeunes Artistes" at the Musée d'Art Moderne de

la Ville, Paris. As for Arnaldo, in 1959, which saw the beginning of series such as Tavola dei segni and Colonna del viaggiatore, made his first trip to New York and San Francisco, exhibiting in 1960

in "New Forms-New Media 1" curated by Lawrence Alloway at the Martha Jackson Gallery, New York, and laying the foundations for the "New Work from Italy" exhibition at the Bolles Gallery in San

Francisco that took place in 1961, which was a crucial episode in the Continuità story.

Like their Roman counterparts, they too felt the need to claim a recognisable space for their own work, dialoguing with the lively surrounding debates, never reduced to constellations of individual

positions, which would have been necessarily fragile.

Certainly, their guru was Lucio Fontana, who, amongst other things, in 1959 presented his "cuts" at the Naviglio, Milan, and at the Stadler, in Paris. But his vocation to protect with generosity

artists and situations alone is not a guarantee. It needs a consistent and authoritative group.

Spatialism and Nuclear Art were in a falling arc, and Milan 1960 was the year which Piero Manzoni and Enrico Castellani's Azimut proposed a series of clearly innovative exhibitions, cumulating in "La

nuova concezione artistica", Miriorama by Gianni Colombo and companions started a series of exhibitions, "Opere d'arte animate e moltiplicate", curated by Bruno Munari at Danese, gave accounts of

further experiences, and at the Apollinaire Pierre Restany presented the Nouveaux Réalistes and published Lyrisme et Abstraction.

In Rome, there was "Possibilità di relazione" at the Attico with Adami, Aricò, Bendini, Ceretti, Dova, Peverelli, Pozzati, Ruggeri, Scanavino, Strazza, Vacchi, Vaglieri, where they spoke of "new

tales", with texts by Enrico Crispolti, Roberto Sanesi and Emilio Tadini, and at the Salita "5 pittori. Roma 60" with Angeli, Festa, Lo Savio, Schifano and Uncini, prefaced by Restany after a

Bolognese anteprima introduced by Emilio Villa.

In Turin Michel Tapié founded the International Center of Aesthetic Research and published, by Pozzo, Morphologie autre in 1960, whilst at Notizie there was an exhibition of the "Laboratorio

Sperimentale di Alba" by Pinot Gallizio.

Those artists thought that a manifesto or shared programme were not necessary, nor a reference gallery. But a group yes, that was essential, to guarantee clear visibility to their own research

horizons.

The occasion was the exhibition of new Italian art that Arnaldo Pomodoro was "planning and selecting" – I cite the catalogue – at the Bolles in San Francisco. This was inaugurated on the 21 February

1961 with the title "New Work from Italy", thus in the same days as the Roman exhibition prefaced by Argan, which we have mentioned, and, with only a partial overlap of names, this was still a sort

of perfect counterpart: here exhibited Bemporad, Carmassi, Dangelo, Dorazio, Fontana, Moreni, Novelli, Arnaldo and Gio' Pomodoro, Sottsass jr.

"Since the felicitous experience of Futurism, Italy has never known such a period of unrestricted and unprejudiced tension as the present. In an international environment every preordained system has

been eliminated; painting and sculpture

are now arts which have transcended all the traditional limits, and the boundaries circumscribing any artistic activity have the tendency to disintegrate because they are in a continuous state of

expansion. It is this vitality and this determined receptivity to new ideas which give a distinct physiognomy to contemporary Italian art, even if at times the voices vary and seem discordant. But

the contrast, in the last analysis, is always the result of a probing search for truth and not for beauty – the truth of a changing, provisory and disquieting existence of innumerable aspects". Thus

wrote Guido Ballo in the catalogue.

Both Argan and Ballo underlined that we are dealing with definite individualities, more than poetically linked authors.

Over the previous decade, the operation of grouping artists by similar qualities rather than ideological, thematic, stylistic or modal congruencies could count on non banal precedences.

Breaking new ground was the Otto pittori italiani group discovered in 1952 by Lionello Venturi in a difficult critical exercise of differentiation as much geometric formalism as art autre. Already in

1957 however, Tristan Sauvage (Arturo Schwarz) had openly underlined how we were dealing with a "tactical regrouping" to safeguard the character and the formal positions of the single authors.

Nor should we forget, in a horizon of explicit abstract-naturalistic settings, the initiatives of Marco Valsecchi on the Dodici pittori italiani, presented in 1953 at Milione, Milan (where he writes:

"First of all it is necessary to say that the artists presented at this exhibition are not bound by any group ties or manifesto, for this meeting it suffices their common aim to interpret the present

time which immediately calls into question the values of absolute and essential order"), which the chronology clearly shows to be a reply to the Venturian choice, and the publication in 1958 of

Trentaquattro opere della giovane pittura italiana, again for Milione.

In the American exhibition the sign of Arturo Carmassi (of which Gillo Dorfles indicated in 1960 rising moods of monochrome) and of Mattia Moreni (who is a survivor of "Documenta 2", like Gio' and

Dorazio) is born from naturalistic zone but evolves into a close reasoning on the substance of the image. That of Sergio Dangelo and Ettore Sottsass jr. sprang from the history of Nuclearism, whose

last declination, the exhibition "Arte nucleare 1957" at Centro San Fedele, Milan, were also Bemporad and the Pomodoro brothers, with Piero Manzoni, Yves Klein and others. Piero Dorazio had passed

from the season of Forma to a 1960 in which he was among the protagonists of "Monochrome Malerei" at the Leverkusen museum curated by Udo Kultermann, with, among the others, Fontana, Klein, Piero

Manzoni, Mark Rothko. Novelli, it is said, was the bridge with the "L'Esperienza Moderna", where Fontana and the Pomodoro brothers were also at home. He comes from non-Italian practices and culture,

in the strict sense, and of the surreal inclinations he maintains the value of an operational continuum that does not erect structures between biography and creation, between the highs and lows of

experience, between brooded flows of the mind and ordinary accidents.

In the reasoning of those days, which can be presumed to be really dense, there is a growth of the interpretive relevance of the "continuum" indicated in Argan's Roman text, which is taken as the

unifying key of an authoritative group, capable of claiming even the reasons of the pictorial and sculptural typicality, as its exponents are implementing on a level of indisputable qualitative

tension.

The Milanese and Romans decided to merge their efforts into a single group, which thus takes the name of Continuità and the reference to the primary reading offered by Argan.

The first outing is on the 12 April 1961 in Turin, at the La Bussola gallery in via Po.

Immediately after the war and in the early 1950s Luigi Carluccio, careful critic with wide horizons, had made that gallery one of the few Italian places with a real international openness, giving it

a prestige that had lasted intact: in 1960 it held a one man by Jean Dubuffet, and in 1961 one by Jean Le Moal.

The first Continuità exhibition fully engaged with the direction of attention to new art. The five authors who had exhibited in Rome – Consagra, Dorazio, Novelli, Perilli and Turcato – as well as the

primary core of the exhibition in San Francisco – Fontana, Bemporad, the Pomodoro brothers – took part.

Argan's text largely repeats the one he wrote for Odyssia, updated, of course, in the paragraphs concerning the single authors.

Some ideas are inescapable. Firstly, the value of space as prevailing over that of form, conceived as a tension to contradict the same convention of the surface and of the picture as the canonical

area of events and of a different vision. Form understood as forma formans, genetically open and alive compared to the neutralised stability of the forma formata, thus as a record of the experiential

continuum of the author and of the viewer, in full autonomy of the sense of the work and its elements, the sign in the head.

The assumption of responsibility in the ethics of doubt, of the questioning, the absence of intellectual and esistential certainty is experimented in the creative process, because, to evoke Carlo

Emilio Gadda, "our sentences, our words, are moment-breaks (landings to rest on) of a cognitive-expressive fluence (or ascent)", carries in itself a character of profound change compared to the terms

of current debate: it does not articulate pre-packaged ideas but authentically searches, with a critically active air, compared to the same primary instruments of art making.

In the midst of the Continuità season, the investigation by Achille Perilli and Fabio Mauri Morte della pittura? for the "Almanacco Letterario Bompiani" offers some important ideas for this order of

reflections. For Turcato, accustomed to proceeding for poetic illuminations more than ordered analysis, painting is now "a new way of being and investigating". For Novelli it is "the death of form

and thus not of painting that, in fact, I think is taking on the appearance, in these days, of a new language that is more complex and more human. It is like when a language changes due to the

enrichment of its alphabet. If it is possible today to find a new way of speaking in certain way of painting, and distinguishing it from the traditional painting of images (Rothko, Burri, Tàpies,

etc.) this is certainly a sign of vitality". The reply by an avant-garde musician, Franco Evangelisti, certainly closer to the international than the Italian scene, is of great interest: "Then we

could move from the centuries old staticity of the figure, into a new expression that binds the image to its shaping spectra, image seen as light-colour energy, in a continuum of transformations and

modulations".

The works published in the Turin catalogue speak perfectly about the moment. Numero, 1959, by Bemporad is a weaving of monemes in coloured matter, iterated in a tissular centripetal/centrifugal

movement to define a theorical all-over. Coro impetuoso, 1958, by Consagra acts on the frontality of sculpture – a theme that will always be important for him – for overlaps and ruptures, in which

the geometrical and organic movements act as lines of strength. Cuore romano,1960, by Dorazio is a uniform weaving of chromatic signs that prevail over the superficial tension to become their own

primary relationship, a sensitivity whereby the optical is transcended by the emotive, in a sort of expanded adimension, that however does not undermine the physical and conceptual boundary of the

painting. Fontana, first amongst equals, had a Concetto spaziale, 1960, in which a sequence of holes decide the entire space, like a tension on the threshold of the infinite: "I perforate, the

infinite passes through there, the light passes, there is no need to paint [...] everyone thought that I wanted to destroy: but it is not true, I have built, not destroyed, this is the thing".

Una delle sale del museo, 1960, says of Novelli that, leaving definitely the "poetry of the wall", he questions in a radiant and caustic way language ("Language has a reality that is independent of

circumstances", he would write in in a drawing of 1963) and space ("What is space? They are the little streets to pass through" he would write in a drawing of 1966). Perilli is near him with La via

del soffio, 1960, in which Nello Ponente, right at that moment, observed that "the sign has no longer any meaning of a scratch [...] it stands to indicate the relationship, the vital ligament between

the surfaces, and therefore between the dimensions that overlap and intersect". Arnaldo Pomodoro published Tavola del matematico, 1960: "I have never neglected to engrave the cuttlefish bones. And

that's how I built, as mosaic, my first Tavola della memoria, that I call Una porta per K (it was the door for Klee, for Kafka, for Kierkegaard). [...] Besides this, I am involved in research with

small reliefs that I call Tavole dei segni", says the artist.

Continuità archetipa, by Gio' Pomodoro, is a plastic page datable to 1959 that seems to contradict the rigidity and the weight of the matter in virtue of the smoothness and the pictorality of the

surface. The signs that irritate such smoothness, the ruptures that contaminate it, the compact game of the cavities and the convexities and the intrusion of small plastic accidents to contradict the

homogeneous aspect, activate an element of drama and accentuate the dynamism of the works.

Turcato, finally. Whose Ritrovamenti, 1959, testifies to the phase in which the schwittersian inclusions of polymaterial moods take to leave the field to the experience of colour in itself: better,

of an unrelated colour, joined by metamorphosis in metamorphosis to the point of being responsible for, and master, only of itself, and of the area of which it is capable. Visions, therefore, not

images.

In Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius Borges writes: "fascinated by its rigour, humanity forgets and reforgets that it is a rigour of chess players, not angels" and is subject "to the vast and minute

evidence of an orderly planet". Here, to leave the rigour of chess without falling into the trap of mirrors of representation. Continuità is also this.

A few weeks later, on the 20 May, the exhibition reached its second stop in Milan, at the Pagani del Grattacielo gallery in via Brera.

Enzo Pagani was not a trendy gallery owner, but makes careful choices: in those years in his rooms there had been exhibitions by Mauro Reggiani, Jean Gorin, Günter Fruhtrunk, Hans Richter (in

November 1961 there was a one man by Novelli), and bridging 1959 and 1960 there was the fundamental collective "Stringenz. Nuove tendenze tedesche", with Busse, Holweck, Jürgen-Fischer, Kricke,

Mack, Mavignier, Sellung, Vorberg, out of which was born the meeting between the Germans of group Zero and the Italians of Azimut.

The text was again by Argan, who made additional changes concerning the single authors whilst maintaining the key paragraphs. The team of artists remained the same except for the absence of Consagra,

who was being presented by Argan in a large monograph soon to be released for the Editions du Griffon.

The charismatic leadership is even more openly attributed to Fontana, one of whose phrases from the Manifesto tecnico dello spazialismo, 1951, is cited at the start of the catalogue: "Art is not

eternal; when man is finished, the infinite continues".

According to the testimony of Arnaldo Pomodoro, the reason that Consagra abandoned the group was precisely due to the recognition given to Fontana as founder.

The project is perfectly homologous, in the organisational and strategic level, to the Turin initiative.

At the end of the year there was a new instalment in the story. At the Galerie internationale d'art contemporain in rue Saint-Honoré, Paris, a collective was inaugurated on the 15 November which

presented Bemporad, Dangelo, Dorazio, Fontana, Moreni, Perilli, Arnaldo and Gio' Pomodoro, Turcato, as well as Alberto Burri and Giuseppe Capogrossi.

With minor variations, the initiative appears to be a re-edition – mutatis mutandis – of "New Work from Italy" by John Bolles. It was certainly no coincidence that the Parisian gallery was a strong

international reference point for the Pomodoro brothers, who had already exhibited here in 1959: Arnaldo had a one man here also in 1962.

That the exhibition was centred on the Continuità group is obvious, even if the pamphlet produced for the occasion does not mention it. The absence of Novelli may be explained by the way the

exhibition overlaps with the one man by the artist at the Galerie du Fleuve, held between the 7 November and 7 December, with issues relating to the relationship between the two galleries. That of

Carmassi and Sottsass jr. with evident eccentricity of their routes in this period. Conversely, Burri and Capogrossi are authors that, ça va san dire, add specific international weight to the

grouping, adding their charisma to that of Fontana.

The text was entrusted to Franco Russoli, dominant figure of the Milanese scene. The scholar takes a cautious approach, in line with his non co-militant character, not openly siding with any of the

fronts of that time: of when the exhibitions of Nicolas de Staël, 1960, and Hans Richter, 1962, at the Galleria civica d'arte moderna of Turin, remain memorable.

"Tout est resumé dans la vibration inalterable d'une vitalité continue et infinie" can be read amongst other things. The scholar highlighted the elements of plurality emerging from the works of the

present artists rather than factors of similarity. It is clear that these works do not intend to be – representation, affective rhetoric, ideology of method, etc – but for the rest here is simply

stated "la validité d'une oeuvre qui est, et sera, en cours".

We arrive at the 16 June 1962 and the third exhibition entitled "Continuità". It is held at the Levi gallery in via Montenapoleone, Milan, directed by Beniamino Levi and by the critic Franco

Passoni.

"Continuità" is the second exhibition of the newly formed gallery, whose interiors were designed by Vittoriano Viganò (specialist in avant-garde Milanese spaces, from the Apollinaire, 1955, to the

Pagani del Grattacielo, 1958), and was prefaced by Guido Ballo, also author of the text for the exhibition's debut, centred on the tachism of the Canadian school.

We say third exhibition, but in effect, the back cover of the exhibition catalogue declares the exhibitions of San Francisco and Paris to also be Continuità exhibitions. It is also listed the stop at

the Bolles gallery of New York, which on the 16 November 1961 inaugurated its New York exhibition venue, at 206 East Fiftieth Street, precisely with "New Work from Italy".

The lack of a real coordination of the group, whose activity appear in hindsight to be mainly entrusted to the initiatives of Arnaldo Pomodoro and Novelli (who, not coincidentally, the following year

will be protagonist of the 13th exhibition of Levi), inevitably led to defining the scope of the activity in an ambiguous way. This is worth another example: in the document list of the exhibitions

by Achille Perilli edited in 1988 with great documentary care by Pia Vivarelli and Elisabetta Cristallini, the exhibition of February 1961 at the Odyssia was calculated in the block of work by the

Continuità group, which is not, as we have seen, at all improper.

Levi's exhibition offers a further variant of the participants in the team: Tancredi was added to the artists presented by Pagani the previous year.

Even Ballo centres his reading on "an art of conception, in which liberty and rigour, flair and inventiveness make it go beyond the traditional sense of space, that becomes the symbol of progress, of

continuity without limits", recognising however that the rose of the single expressive declinations is wide and varied.

Fontana had a Concetto spaziale of rich matter, scratched and perforated, part of the ones known as "oils". Gio' had Letto del vuoto, 1959, a "surface in tension" that he would declare inspired by

his reflections on Schwitters. Dorazio had Shrine 1, a classic lattice made of density rather than light, Bemporad a Superficie sensoriale of uniform and continuous weave. Even Turcato's La pelle and

Novelli's Tetto del mondo do not demonstrate developments in their work that are worthy of note.

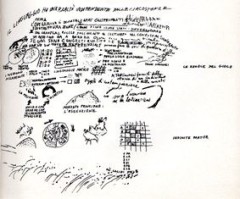

Perilli's Il promemoria del criminale exemplifies his decisive passage, between 1961 and 1962, towards explicit shapes of "pictoric narration", adopting the rhetorical code of the comic strip to

organise a pattern of temporality made into a spatial sequence: it is the context in which real possible stories happen, clotting moods distilled by surreal echoes.

Tancredi, the new entry, with Fiori dipinti da me e da altri - dipinto al 101%, an example of his probably most extraordinary series, before his early disappearance, bring a colourism element which

accelerates even more the predominately pictoral spirit of the group: looking closer, the same Pomodoro brothers operated in this period on an understanding of sculpture as a plastic surface.

Arnaldo, however, with La Ruota, executed an extraordinarily problematic boost towards the complete taking possession of space: this is the fruit of the sequence that associates it to research like

Cubo and Radar, and that cumulates in 1963 with the first Sfera.

The story of Continuità ran its course with this exhibition. The strength of the group was especially that of giving an account of the first maturity of artists already baptized by the events of the

debate. This however was also the articulation of occasions – exhibition, career, market – that inevitably tend to diverge, each being focused on his own way.

A group is, the history of the century has taught us, also, and perhaps especially, the critical management on an organizative and mediatic level: Carlo Cardazzo is the Spatialism Movement, Enrico

Baj is Nuclear Art, Manzoni is Azimut, Restany is the Nouveau Réalisme etc.

For his part Argan, increasingly turned his attention to what is defined Gestalt art, Ballo continued his story of critic/poet.

Each of the artists had links with different market situations, not a single gallery had the strength to be the guarantor of all the group together. And then there are the lives and works, with their

multiple trajectories and different degrees of success.

Continuità can only be what it announced it wanted to be: a collection of singular and strong personalities, and therefore, inevitably, for each of them, a passing phase.

Johnny Moncada, Gastone Novelli, Achille Perilli. Made in Italy. Una visione modernista. Fotografia - Moda - Arte - Design. Roma 1956-1965

edited by Valentina Moncada

The exhibition Johnny Moncada, Gastone Novelli, Achille Perilli. Made in Italy. A Modernist Vision, held in the National Etruscan Museum housed in Rome’s Villa Giulia (from 13 July to 30 September 2014), showcases an extraordinary season in Italia creativity which bloomed in the 1950s and 1960s and focused around a thoroughly modern figure, and a visionary: Luisa Spagnoli.

The catalogue, published for the event, displays the works of the great fashion photographer Johnny Mondaca, made with the backdrops designed by Gastone Novelli and Achille Perilli, next to paintings and drawings of the two artists.

Here below the texts of Valentina Moncada, curator of the exhibition, Ludovico Pratesi and Paola Bonani (copyright of the autors).

The volume could be purchased on the Valentina Moncada Gallery's web site: http://www.valentinamoncada.com/books.html#moncada-giulia

Documento Adobe Acrobat [782.8 KB]

Documento Adobe Acrobat [895.4 KB]

Documento Adobe Acrobat [968.3 KB]

Claude Simon, l'inépuisable chaos du monde

Paris, Biblioteque publique d'information - Centre Pompidou

2 octobre 2013 - 6 janvier 2014

Ci-dessu l'article publié par Dominique Viart, directeur scientifique de l'exposition, dans le n. 12 de "de ligne/en ligne. Magazin de la Biblioteque publique d'information", octobre-décembre 2013, pp. 17-19

Documento Adobe Acrobat [1.4 MB]

Gastone Novelli and Venice: a Chronicle

by Luca Massimo Barbero

(in Gastone Novelli and Venice, exhibition catalogue, curated by L. M. Barbero, Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, October 15, 2011 - January 1, 2012)

Painting also means using marks to express

what cannot be expressed through actions.

Gastone Novelli

Gastone Novelli's work is becoming an object of renewed attention and analysis thanks to the publication of the new general catalogue of his works, which offers the chance to introduce the public of a new generation to one of the most unique artistic itineraries from 1950s and 60s Italy. The artist's career began and matured with extraordinary intensity in just under twenty years of coherent and warmly enthusiastic work, attaining a complex completeness that even today appears strikingly ahead of its times. Novelli's ongoing engagement with the values and problematic fluctuations of the society of his age – his eagerness to enable “a world to express itself” through a language as original as it is universal – opens up new worlds and potential realities before the viewer. Novelli's willingness to present marks to others, to the public, to the eyes of those capable of looking and grasping the thoughts behind them, brings out his constant and free engagement as a visual communicator in love with his own images, marks, words and places – in other words, with a universe enclosing and interacting with society, humanity, and alleged human freedoms. “Painting,” the artist wrote in 1964, “is a personal ritual that stems from infernal needs and addresses a public utterly shrouded in the mystery of numbers and time.” This personal ritual Novelli sought to nourish through a lucid liveliness he occasionally described as being anarchical with respect to artistic currents, art historical labels, and contemporary social conventions. The lucid and “normal” twisting of the artist's marks, as he himself defined it, reflects the quick and allusive – as well as literary and intuitive –depth of his thought and his ability to listen to the world and to society, constantly situating it among those forces serving as a genuine seismograph for the potentials, tensions and sensitivities expressed within the fabric of society as a whole.

It is through this creation of a universe with a potential language of its own that Novelli's entire career unfolded. The aspect of it we have chosen to introduce to the public is the artist's productive relation with Venice – a relation developed through exhibitions as well as the artist's dealings, musings and work in the lagoon city.

Lagoon?

Immortalized in the gesture of turning his paintings over in his room at the 34th Venice Biennale, in the collective memory of the art world Novelli features as one of the protagonists of an international season caught between responsibility and protest. Pictures by Enrico Cattaneo, Ugo Mulas and Cameraphoto indissolubly link him to the sacred contested enclosure of Venice, this island of art. Those works removed from the gaze of viewers and the artist's gesture find their origin and justification in a wider context.

We have chosen to set off from these symbolic images in order not merely to present a partial reconstruction of Novelli's works, but also to explore the connection with Venice which they suggest was fated to mark the close of the artist's career. Venice is seen as a lagoon (appearing in a drawing here on display with a question mark and smoking mount – possibly Marghera?) and natural environment – almost a crucible of ages, styles and cultures. The lagoon city represents a vague space where to seek refuge and exchange views with friends, a labyrinth in which to gaze at erratic sculptures and talk of art.

Novelli was first offered the chance to display his works in 1960. 'Crack' was not simply a group exhibition, but a sort of manifesto and attempt on the part of its artists to clarify their position. This found complete expression through a volume published the same year – a particularly busy one for Novelli, not least on an international level. The exhibition and publication stemmed from the artists' mutual engagement; most importantly, it may be seen to express the thought of Cesare Vivaldi, who in resounding terms stated in a leaflet and then at length in the publication: "Do not ask us to choose, for we reject the means to choose. We reject language . . . . We do not believe in the conventional order of language (syntax, sequences, tones, marks) or in its negative counterpart – the formless.” Even more so than the works on display, this text outlined a new collective position (one nonetheless marked by differences and often even discordances among the works of the artists). It neatly summed up the innovative forms of expression at the heart of the exhibition as a genuine prose manifesto for a new way of thinking. While removed from all critical and academic language, Vivaldi explored the new non-positions with regard to the production of art from the paradoxical point of view of a new language. Echoes are discernible here of pre-Surrealist literature, of Jarry's caustic irony and of Lautreamont's inhospitable fires through new literary and grammatical experiments of the sort that was destined within a few years to characterize the new Italian and European avant-garde movements. Ultimately, these features represented the basis of the exhausted condition of the new generations vis-à-vis the cultural status quo, and not in Italy alone either – positions that later led to the development of a more radical movement of protest. Besides, only a few months earlier the same rooms of the Galleria Il Canale had housed the “anti-procès” event promoted – like all other ones of its kind – by Jean Jaques Lebel under the title of 'L'Enterrement de la Chose de Jean Tinguely' – something which further confirms the contemporary and purposeful nature of the Venetian venue chosen by the Rome-based Crack group.

In April of the following year Novelli returned to Venice, this time for a solo exhibition in the Galleria Il Traghetto. The accompanying publication included a text by Toni Toniato, an important Venetian critic interested in both historically established art forms and new experimental research. In his detailed reading of the artist's language, the critic writes of a “secret irony that goes beyond the unnatural quality of its means of expression . . . beyond the artificiality of the very verbal combinations and symbols of our time." The topicality of Novelli's work – as the text suggests – lies in a sort of “magical moment of the imagination”, as well as in the “mystification” that comes about through this moment. Venice read these words and welcomed Novelli's new works: the artist made his first acquaintances in the lagoon and grew familiar with the Venetian milieu, which could boast a number of critics at the time – from Apollonio to Marchiori and all those visiting critics who would spend long periods of time in the city, frequenting its galleries and restaurants such as La Colomba and L'Angelo, which were almost partisan meeting places for the local art factions. Umbro Apollonio started corresponding with the artist following the invitation Novelli received from the Venice Biennale to exhibit his works in the Italian section of the São Paulo Biennial of 1963 – which he did, with five recent works. These were busy years for the artist: museums started displaying his works and his personal itinerary was much appreciated in Italy. His thoughts drew upon the apotropaic and magical images of the Indians of the Americas, the experimental research of his writer friends and his first trip to Greece, destined to become a crucial epic journey for him.

So we might talk of painting as the expression of

a possible and, if you like, arbitrary universe

Novelli's career culminated in his invitation to the International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale of 1964. Here he displayed his latest achievements, including Il Gioco dell’oca (The Game of the Goose) and Il Vocabolario (The Dictionary), on top of Barcellona (Barcelona). The artist's experiments with image-writing in those years – his poised work on the surfaces of writing marks – broadened his visual field and provided a new seignic universe through an extended and serenely original narrative developed according to possible archetypes. “Since I believe in the existence of infinite universes, meaning I believe any universe to be possible,” Novelli stated in an interview with Enrico Crispolti concerning his room at the Biennale, “mine is an engagement with a specific universe, the expression of a certain kind of possible universe.” On this occasion, Venice witnessed the grand entry and consecration of American Pop Art. Starting from his very statements, Novelli independently took up a stance antithetical to that which he described as “an event-based form of painting . . . since it is often automatically connected to some news. . . . In other words, painting that seeks to fit within society by finding a functional justification for itself.” Novelli, by contrast, had developed a new, lofty and complex form of narrative: a new language that found expression in his works at the Biennale. The artist's narrative was based on “extremely detailed means, enabling one to perfectly attain a language through which to recount and express oneself.” This same year, Novelli founded the magazine Grammatica with Giuliani, Pagliarani, and Perilli. He also worked with his friend Manganelli and published Das Bad der Diana, featuring a text by Pierre Klossowsky. The artist's horizon was an international one: through his travels (to Turkey and New York that year) he defined new possible narrative visions. At the Biennale he received the Gollin Award for young painters. Short and valuable exchanges from this period between Novelli and Dell’Acqua, as well as Apollonio, are preserved in the archives of the Biennale. We also find some suggestions and requests the artist made to the architect Carlo Scarpa, who was responsible for designing the event in Venice. The city was still a lagoon environment, almost an island to itself, from another age, in a world about to undergo revolutionary changes.

BREK!

A manner-sound of avoiding (tedious) conversations

For a few years in the artist's life, Venice was only a place for short visits and exchanges. His exhibit schedule grew and his works progressively acquired the kind of lively “ambiguousness” which critics will usually seek to exorcize on account of its originality. Novelli's work resisted all definition other than the scrutinizing of its woven narratives, engagement with others, and setting of new horizons. What proved most baffling and yet persuasive was Novelli's “wary lightness”, as Galvano wrote on the occasion of the 1967 exhibition at the Galleria La Bussola in Turin – his manner of proceeding through a “reversed game, innocence lost at the roll of dice.” New interplays emerged on his canvases and wondrous sheets, assonant meanders devoted to terrifying and charmed viewers, trails of kites against perennial and living skies, a thousand words picked up and translated – the settings for new marks for new possible human astrologies.

One of these sounds, 'Brek' reached Venice in 1967. Held in the Galleria Barozzi in Rio Terà dei Catecumeni, this exhibition also illustrated the publication the publishing house Alfieri was issuing in those days: an adventure in the form of comic strip-words, a heroic new beat and at the same time the very opposite of all this. Suffice it to flick through the pages of Brek – now available through the present exhibition – to immediately share the artist's free obsessions, what he drew from television, his ironic and free eroticism, his gaze constantly focused on the latest popular culture that makes the headlines. Novelli's new images must have struck his contemporaries in Venice, including art dealers, as rather original and unusual. At the same time, they fit within a broader tendency in those years to view the use of words and writing as a new field of action, a field Novelli had long been exploring. Ultimately, the Brek the artist had in mind was a break that would enable him to discover a new silence through which to hear things again, end the annoying chatter, and rediscover the significance and incisiveness of words: a new way of voicing opposition and quietly protesting.

Between 1967 and the beginning of the following year a series of events took place, with the artist no doubt becoming fully aware of his means of action and self-expression. Several exhibitions were held, including important international group ones – such as those in Graz and Ljiubljana – as well as a solo one in Genoa, the significant, if not crucial, solo exhibition in the Fine Arts Museum of La Chaux-de-Fond in March 1968, another solo one in the Toninelli Gallery in Milan in April, and finally 'Peintures' in the Semiha Huber Gallery in Zurich in May. The invitation to the last of these exhibitions also announced the artist's forthcoming participation in the Venice Biennale.

My work is so secret and useless perhaps

that it tolerates no second thoughts.

Venice, an enclosed and fertile space, became an obsessively recurrent feature after 1967. When Novelli reached the city, he was confident a new season had begun, one he did not hesitate to describe as a profound crisis. In this case too crisis took on the fervent splendour of new images and torments soothed by finding release on new sheets, notes, and canvases. These works were chiefly conceived in the artist's studio in the Casa dei Tre Oci building on the Giudecca, an environment shaped by artistic touches and visions ever since it had first been designed by Mario De Maria, the night owl Marius Pictor. Venice thus became a sort of repository for Novelli's new works, in which he could assemble his creations. A notebook with some drawings executed in the city is on display in the present exhibition: some have the lagoon as their subject, while others show light and graceful views of mysterious landscapes, like small dream mountains floating on celestial waters, transposed geometries suspended through pencil strokes, deliberately imprecise and mathematically inexact. In one notebook Novelli transcribed – in a dense and overcrowded column – a newscast from the Veneto that appears almost encrypted and translated, as if to gain control of an unknown territory marked not just by its history, but by terrible elements. The artist jotted down the number of cars and car accidents in the Veneto, the Albanian trade, the overwhelming of history by news. This power of the news as an indicator of the development of society became a feature of Novelli's work: gradually at first, as a transposition from everyday life, and then as a source in itself – a necessary, vital and destructive one. Thus the artist began exploring major themes of protest, or rather of possible transposed denunciation: conflicts, acts of aggression against the world and nature, fights and wars. The artist's “Venetian” works unfold between the two poles of his dialectic: on the one hand, his consistent need to publicly share, offer and convey the vastness of the tensions in the world; and on the other the need to lend shape to his own perceptual universe – wings drawn on images.

This direction taken by Novelli's career is illustrated by the small-size works here on display: unpublished items from a Venetian collection that are here presented for the first time. A world comprised of new and almost tangible, perceptible geometries surface in some of the works from 1967: intelligible perimeter marks create an increasingly hallucinatory white suspension. It is the appearance of white, permeated by emerging marks, that seems to define this creative moment. In certain works, by contrast, the colour sustains the artist's vision, lending it definition and concreteness, as if to form an impeccable and extended blending of marks. Il gioco dell’oca is featured in Il rito dell’amore (The Ritual of Love) like an insidious yet wonderful snare laid by destiny. The optical unfolding of Piccolo mondo della geometria (Small World of Geometry) finds itself compressed and suspended in Vitalità del cubo (Vitality of the Cube), which in turn spreads out as the disconnected and levitating matter hinted at in Caos nell’aquilone (Chaos in the Kite). A good enough introduction to the artist's studio in Venice may already be found in the theme and density of a small work such as L’uomo che annega nel proprio sangue (The Man Drowning in His Own Blood), a warning and recording of an instant conveying symbolism, an acute sensibility, the suffering of the world and its betrayed potential. It was in this spirit that Novelli – fatally, we might say today – prepared the works for his room at the Venice Biennale of 1968. He chose a work from 1966, Viaggio nel Paese delle meraviglie (Travel to Wonderland), and Indian curios, executed in 1967; the other works he specifically created for the Biennale that year, a particularly busy one in terms of exhibitions – almost the high point in the artist's career. All these works were striking and significant, revealing as they were of Novelli's personal dialectic, one that “entails no second thoughts”.

Hieroglyphs today are steeped and interpreted in abstruse, concealed terms.

René de Solier

Novelli's room at the Biennale was a place of warning expressing the artist's hope of being heard, of communicating with man and of offering him sad signs that might be read and heard – not just muffled sounds. If the possible fall of man also entails a linguistic fall, a new language might reverse the fall of civilization itself or at least promote a new awareness of it. It is as though within this new language the signs marking the artist's new works had been created specifically for modern man, while at the same time forming a speech to be scattered by the wind of history and an unspeakable destiny. This is the direction de Solier would seem to have in mind when he writes that: “he thinks not so much of graffiti as of alphabets. He needs colour for his letters, not forms already known and tested. . . . In painting one loves networks, colour-glyphs, and dense elliptical texts." In his paintings for the Biennale, the artist conveyed this density through imposing fields of silent white. Novelli marshals ivory heralds – vertically arranged, for the most part – for a frontal, immanent reading that extends upwards or else tends to sink against the perimeters of teeming surfaces. Vertical and allusive, his Onfali (Navels), forgetting Herculean heroism, had to face the challenge of the static quality of the room, like sculptures and epic echoes of the obelisks the artist alluded to in his works. “The artist becomes an anagrammatist, his alphabet sculptural,” again de Solier writes. The cry of Dio è nemico dei prati (God Is an Enemy of Meadows) and the visual consideration expressed by L’Oriente risplende di rosso (The East Shines with Red), along with the other works displayed, represent a lofty and lyrical ongoing pursuit of painting with the fervent persistence of doubt as its subject and recipient.

Novelli's days in Venice unfolded with exciting leisure, as news reached the lagoon city of the occupation of the Triennale in Milan and of the first student protests. Carrain's All'Angelo restaurant in Calle Larga San Marco, which twenty years earlier had been the haunt of the Fronte Nuovo delle Arti, now served not just as a venue for discussion but as an apparently safe harbour. Those days witnessed increased debates among the city's artists, critics and art professionals concerning the June event. Novelli began arranging his room, while practically at the same time the police started patrolling the Biennale and St Mark's Square and the city's alleys turned into the setting of demonstrations organized by the young, including art and architecture students. In a cyclostyled letter addressed to Novelli, the Student Movement of the Fine Arts Academy submitted “a formal invitation” for the painter to withdraw his works from the 24th Biennale.

Novelli, however, had already made up his mind. The artist penned a lucid statement betraying his marked awareness of the irreversibility of his own position: “Painting means operating within a language – it is the search for a possible universe, not an attempt at popularization. Refusing to exhibit one's works at a regular Biennale today would be nothing but a useless act of exhibitionism. . . . The reason why it is really impossible to exhibit one's works at the Biennale today is that it has become the stage of a power struggle between a police state and its opponents.” The room featuring Novelli's new works served as his manifesto: the real expression of this rejection on his part – a choice consistent with his way of thinking and adherence to nothing if not the genuine roots of a possible and perhaps utopian new society. Some of Novelli's works were turned over, others covered; the paper employed by the artist, just like the back of the canvases, was used for writing slogans such as No to all forms of violence! and Down with the fascist Biennale!. Photographers committed these moments to memory, as if they were performances, while the press significantly presented them as a shocking event. Confident in his clear-headed calmness, the artist was portrayed through these words and pictures as in a desperate gesture he turned his paintings “with their face to the wall”, concealing them from the public. Silence fell over the room he had “believed in”.

(Copyright LMBarbero)

A catalogue of lost things

by Marco Rinaldi

(in Gastone Novelli and Venice, exhibition catalogue, curated by L. M. Barbero, Venice, Peggy Guggenheim Collection, October 15, 2011 - January 1, 2012)

The word catalogue first appeared in a work by Gastone Novelli in 1957. Un catalogo di cose perdute (A Catalogue of Lost Things) is a painting in which tentative signs, gestures and blotches emerge from a magmatic surface with a flavour of the unconscious. The title anticipates the exploratory and taxonomic work that the artist would carry out some time later, when barely delineated signs and scribbles would begin to turn into fragments of writing, gradually becoming increasingly complex and combined with colour-fields or with a chalky white that often absorbs or erases them. Alphabets, vocabularies, catalogues, cosmographies, treatises on anatomy, and writings drawn from many tongues and languages, some of which have been lost, such as the signs on the Phaistos Disc, or oriental and alchemical symbologies, and finally myth, would lead to the creation of that magical and anthropological world in which all universes are possible. The invention of unexplored places and territories, like the soul, the recovery of spaces forgotten in the recesses of mythologems and archetypes, create poetic worlds that spread out and turn in on themselves. The hesitant process of writing, error, lapsus, erasure and suddenly intense or reduced colours, all follow the same stream of consciousness that Novelli seems to share with much contemporary literature, such as that of James Joyce, and particularly Samuel Beckett.

His paintings often take the form of maps, in which arrows and numbers seem to indicate the direction to follow when reading them, while coloured grids and checkerboards scattered with signs, letters, and again numbers function as legends; at other times the writing spreads everywhere, inundating the canvas with fragments of sentences in different languages that follow a path similar to that of contemporary poetry. Language turns in on itself and takes labyrinthine routes that are progressive and retrogressive; letters and words at times are written backwards, treated almost like dodecaphonic series. Like the game of snakes and ladders, Novelli’s pictorial research, which coincided with his intellectual venture, was marked by accelerations and regressions, pauses and crises, which over the years manifested themselves through the appearance and reappearance of iconographic themes, or variations and reprisals of stylistic motifs: mountains, planets, erratic flights of kites, reduction to monochrome, calligraphies that become decorative patterns, the pulverization of colour and the reduction of writing to the slogans in the 1967-68 political paintings.

The artist’s passage through so many linguistic universes – from the unconscious to myth, from depth psychology to poetry, from alchemy to Eros, from structuralism to Trotskyite and Maoist ideology – in its winding path, may have found a common denominator in an approach that was first instinctively and then consciously anthropological, which led him to constantly and compulsively collect wide-ranging cultural materials. In fact, from his years in Brazil on, Novelli sought to combine the modernist ideology of a country in ferment with Indian culture; on his return to Rome, the rationalist and geometric layout of his works was tempered by compositional solutions that indicate familiarity with certain atmospheres associated with the Gruppo Origine. Next came the encounter with Japanese calligraphy, with the poetics of the sign and the gesture, and the discovery of the unconscious. At a certain point, all these influences crystallized in the proliferation of dense and fluent writing that led him to explore a vast world of signs composed of the fragments and traces of many languages, which Novelli collected, preserved, catalogued and reassembled like a bricolage. It was the discovery of Jungian analytical psychology, of myth, but also of Claude Lévi-Strauss’s structural anthropology. The resulting magical language is semantically indeterminate and ambiguous, which is typical of poetry, but elements of mass culture are often brought into play.

His broad receptiveness to contemporaneity led him to ultimately embrace the echoes of the Chinese Cultural Revolution and the ferments of 1968, a period that closed with the well-known affair of the 1968 Venice Biennale, and which was also marked by a painful crisis for the artist, shortly before his untimely death.

Novelli also catalogued his works, and the records that he left have been a precious instrument for reconstructing and organizing his pictorial and plastic production. The general catalogue attempts an actual reconstruction of the difficult and tormented artistic and personal trajectory of this artist, “a journey made by a lone individual”, as Gianni Novak wrote, together with other “lone fellow travellers”, Lautréamont, Arthur Rimbaud, André Breton, Alfred Jarry, Georges Bataille, Pierre Klossowski and Samuel Beckett. Writers whom he loved and with whom he sometimes followed the same path through language, collecting many lost things along the way.

(Copyright M. Rinaldi)

Novelli et les écrivains français

par Brigitte Ferrato-Combe

(in Gastone Novelli, catalogue de l'exposition, Paris, Galerie di Meo, 10 octobre-20 novembre 2008)

Entre 1956 et 1961, Gastone Novelli, déjà reconnu en Italie comme un des principaux représentants de l’avant-garde, fait de fréquents séjours à Paris. Il y rencontre des peintres (André Masson, Hans Arp, Man Ray) mais aussi des écrivains (Samuel Beckett, Georges Bataille, Claude Simon, Pierre Klossowski, René de Solier) avec lesquels s’établit un dialogue dans la création. Il illustre plusieurs textes d’écrivains français : Comment c’est de Beckett, Histoire de l’œil de Bataille, plus tard Le Bain de Diane de Klossowski. Certains titres de tableaux gardent la trace de ses lectures.

L’exposition qui lui est consacrée en novembre 1961 à la Galerie du Fleuve le fait connaître en France comme un représentant de la « nouvelle figuration » et met en lumière « l’intégration de lettres, de graphismes à sa peinture » en même temps que leur « vertu plastique », comme le note le critique Michel Ragon.

L’année suivante, le romancier Claude Simon, avec lequel s’est nouée une vive amitié, retrouve Novelli à Rome et rédige à sa demande une préface pour l’exposition présentée à New York par la Galerie Alan en novembre-décembre 1962. Ce texte s’intitule de façon paradoxale et significative : « Novelli ou le problème du langage ». Passionné de peinture et lui-même engagé dans la recherche d’une nouvelle écriture romanesque, Simon voit dans l’œuvre de Novelli un « merveilleux et aveuglant labyrinthe de signes dont on ne peut sortir », « des fantasmes de chair et de songe élaborés par la mémoire dans, avec et à travers le langage ». Très sensible aussi aux qualités picturales de cette œuvre, « avec sa matière crémeuse épaisse, ses subtiles modulations de tons et ses colorations éclatantes », il la considère comme « une des plus surprenantes et riches recherches picturales et graphiques », et comme exemplaire des tentatives menées par beaucoup d’artistes – peintres ou écrivains – pour recommencer à créer par delà le traumatisme de la deuxième guerre mondiale:

« Après la guerre, dit avec pudeur Novelli (il ne dit pas l’enfer, le néant, la mort de Dieu et de l’homme, le « degré zéro » de tout, l’univers des camps et de la violence criminelle), il fallait nécessairement recomposer une esthétique, reconstruire une civilisation. »

Et comment repartir de zéro, si ce n’est en prenant comme support les matériaux élémentaires, les seuls certains, les plus pauvres, les moins équivoques ou récusables: le plâtre, la terre,

le sable …

(Copyright B. Ferrato-Combe)

Anmerkungen zum Werk Gastone Novellis

„Als wollte man mit einem Alphabet schreiben, das es noch zu erfinden gilt“

Andreas Hapkemeyer

(in Gastone Novelli, exhibition catalogue, Bozen, Galerie Les Chances de l'Art, 19 aprile-20 maggio 2006)

I.

Aus der Distanz betrachtet erscheint Novelli als einer der eigenwilligsten Künstler, die Italien in den 50er Jahren hervorgebracht hat. Sein Werk ist sperrig, da komplex und vielgestaltig, und erschließt sich daher nicht leicht. Das mag auch einer der Gründe sein, weshalb Novellis Werk sich – wie schon Achille Perilli 1976 im Vorwort zu dem Novellis Schriften gewidmeten Heft 5 von „Grammatica“ beklagt – wesentlich weniger durchgesetzt hat als dasjenige anderer, oft weniger interessanter Zeitgenossen.

Novelli hat sich in zahlreichen, meist kleineren Schriften über seine Kunst und die Kunst im

allgemeinen geäußert. Wenngleich diese Texte partienweise kompliziert und dunkel sind,

geben sie an vielen Stellen Aufschluss über sein Werk und dienen als Orientierungshilfe. An

dieser Stelle soll ausgehend von seinen durch Achille Perilli herausgegeben Texten auf einige

Punkte in Novellis Denken hingewiesen sein, die von grundlegender Bedeutung für sein Werk

sind.

II.

„Ich lag ausgestreckt auf dem Asphalt. Sie wollten mich überfahren, das war ein neues und unterhaltsames System, um jemanden zu töten. Der Motor des Lastwagens begann schneller zu drehen und kündigte mir meinen nahen Tod an. Die Räder rollten an und ich hatte bereits das Gefühl, meine Knochen brechen zu fühlen.“ Dieses Zitat stammt aus Novellis Aufzeichnungen der Jahre 1943/44. Unmittelbar vor der Ergreifung durch seine Gegner hatte er selbst versucht, einen Gegner zu töten; ein Freund von ihm verliert bei diesem Kampf das Leben. Der Lastwagen, der Novelli töten soll, bremst knapp, bevor er den am Boden Liegenden erreicht. Der Gefangene soll noch verhört werden. Er kommt in ein Gefängnis der deutschen Besatzer bzw. der Faschisten und wartet auf seine Hinrichtung, während aus den umgebenden Zellen immer wieder Gefangene abgeholt und gefoltert oder getötet werden. Es sind die am eigenen Leib gemachten Erfahrungen des Krieges, der Besatzung und der bürgerkriegsähnlichen Zustände in Italien, die Novelli – wie viele Altergenossen nicht nur in Italien – zutiefst prägen. Das Leben eines Menschen hat in Zeiten, in denen die größten Kräfte aufeinanderprallen und Millionen sterben, einen geringen Wert. Solche Erfahrungen lassen ihre Spuren. So gesehen ist es keine Rhetorik, wenn man vom existenzialistischen Zug der Kunst der 50er Jahre spricht, jedenfalls nicht bei Gastone Novelli. Es handelt sich nicht um ein (rein vorstellungsmäßiges) Vorlaufen zum Tod im heideggerschen Sinn, sondern um die unmittelbare Begegnung mit der Möglichkeit des eigenen Todes, welche – ohne dass das immer wieder gesagt werden müsste - die Perspektive im Werk eines Künstlers bestimmt. Man geht wahrscheinlich nicht zu weit, wenn man hier auch die Wurzeln des politischen Engagements für die Linke sucht, das Novellis letzte Lebensjahre kennzeichnet.

III.

Mit der eben angesprochenen existentiellen Grunderfahrung hängt auch ein zweiter Zug zusammen, der Novellis Werk ganz wesentlich bestimmt und bei der Betrachtung seiner Werke immer im Hinterkopf zu halten ist. Gemeint ist hier seine Hoffnung, dass die Gesellschaft, aber auch die Kunst nach dem Desaster des Faschismus und des Weltkriegs noch einmal ganz von vorne anfangen soll. Spätestens seit den 50er Jahren steht sein Werk gänzlich im Zeichen einer Spracherneuerung, die der Künstler selbst als Spiegelbild möglicher gesellschaftlicher Veränderungen sieht.

Die Suche nach einer neuen Sprache, welche auch die Konventionen und Plattitüden der Kunst – denn auch dort gibt es sie – überwindet, ist eines der großen Anliegen einer ganzen europäischen Generation. „Keine neue Welt ohne eine neue Sprache“, heißt es etwa bei Ingeborg Bachmann, die um 1960 ebenfalls in Rom lebt, ohne aber je nachweislich mit Novelli zusammengetroffen zu sein.

Novellis Text“ L’uomo coyote“ (Der Kojotenmann) setzt nach Art eines Märchens ein mit der Ankunft des Koyoten und des Fuchses auf einer leeren Welt. Die Welt, die Kojote und Fuchs vorfinden, ist das unbeschriebene Blatt, für das es erst einmal die richtige Sprache zu finden gilt. Nach dem märchenartigen Auftakt geht die Diktion des Textes in diejenige einer Abhandlung über: „Zunächst war es notwendig, die Instrumente, die Alphabete, Zeichen, Fragmente zu katalogisieren, um dann zu ihrer Organisation in einer Struktur, zu einem grammatischen Ganzen fortzuschreiten, das man analysieren kann und das eine Art Präzision hat./ Zeichen sind gleich konkret wie Bilder, Buchstaben gleich konkret wie Wörter, aber sie haben die Fähigkeit, Bezüge herzustellen, auch wenn sie sich grundsätzlich nur auf sich selbst beziehen, sie können an die Stelle von etwas anderem treten.“ Daher sei es wichtig – so der Text weiter -, von den Zeichen und den Buchstaben auszugehen und nicht von Bildern und Worten. Man kann wohl annehmen, dass Novelli sich hier auf den Vorgang der Lektüre von Werken bezieht: dieser Reihenfolge folgt der ideale Interpret.

Novellis Ziel ist die Entwicklung eines neuen Zeichenuniversums, in dem Bekanntes einen neuen Stellenwert einnimmt. „Jedes Universum ist eine mögliche Sprache, ‚magische Sprache’ und nicht ‚akademische Sprache’, ‚universitäre Sprache’; der Unterschied liegt darin, dass letztere von bereits existierenden Systemen ausgeht, um zu etwas Eigenem zu gelangen, dagegen erarbeitet die ‚magische Sprache’ ein strukturiertes System, das auf Überbleibsel und Fragmente zurückgreift, auf ‚fossile Zeugen der Geschichte, des Individuums oder der Gesellschaft.“ Die Werke, die seit Ende der 50er Jahre entstehen, wirken alle auf die eine oder andere Weise an der Entwicklung dieses neuen Universums mit. Novelli geht es darum, über Zeichen und Bilder, Buchstaben und Wörter, die insgesamt Komponenten einer magischen Sprache sind, die ihn umgebende Welt einzufangen, wobei es keine scharfe Trennungslinie zwischen Gegenwart und Vergangenheit, zwischen Individuum und Gesellschaft, zwischen Rationalität und Intuition gibt.

Wichtig für das Verständnis des durchaus intellektuell begründeten Werkes von Novelli ist seine 1958 gemachte Äußerung, dass er seine Kunst (ganz konkret seine Wand-Schriften) im Zeichen des Nicht-Wissens sieht. Es geht um eine Überwindung des bereits Gewussten, des Gewohnten, in unserer Vorstellung Verfestigten. Das Nicht-Wissen ist die Voraussetzung dafür, das eine neue Welt entstehen kann: daher auch der Verzicht auf zeichnerische Meisterschaft wie sie –anders – auch das Werk von Cy Twombly charakterisiert.

In seinem Text „Malerei, die vom Zeichen ausgeht“ aus dem Jahr 1964 schreibt der Künstler: „Als erstes Linien ziehen, (wie die Etrusker das Feld) die Landschaft des Menschen ‚auf eine Fläche‘ ritzen, das Meer, die Wellen, Vibrationen, den Wald der Worte. Wie die Hieroglyphe, welche die Säule begleitet (ziert), manchmal oben, manchmal unten, meist in der Mitte. Der Buchstabenblock oder der große schachartige Teil rechts im Bild steht für das, ‚was entsteht bzw. entstehen lässt‘, auf die Füße stellt, aufbaut, ans Ufer anlegt, den Anker wirft. Und dann: Epigraphen (am unteren Rand der Leinwand): eine Sentenz, die ironisch den dominanten Gedanken des Werkes aufnimmt; Legende: zirkuläre Inschrift im positiven Sinn, von links nach rechts (bei unterschiedlichen Geschwindigkeiten); Proklamation: Operation: geboren werden, operativer Wert, aufstehen (orior) etc. ...“

Wo durchgängige Sätze oder Texte in Novellis Bilder eingefügt sind – es handelt sich meist um tagebuchartige Aufzeichnungen –, ist für eine adäquate Rezeption eine aufmerksame Lektüre erforderlich. Aber Bedeutung entsteht nicht erst über syntaktisch vollständige Aussagen. „Die Art der Schreibung kann nämlich den Wörtern weitere oder andere Bedeutungen vermitteln, so wie eine Zahlenreihe die Leserichtung bestimmt, mit notwenigen und unterschiedlichen Pausen je nach Regelmäßigkeit bzw. Abweichung von der üblichen Reihenfolge. Sätze und Wörter hingegen zwingen zu einer Lektüre mit festgelegter Richtung und Dauer entsprechend den Schwingungen, Auslöschungen, Überdeckungen, Verformungen.

IV.

Wie seine italienischen Kollegen, die nach Kriegsende Anschluss an die internationalen Entwicklungen suchen, arbeitet er anfangs geometrisch; in der zweiten Hälfte der 50er Jahre berührt er mit seinen Bildern das – damals bereits im Niedergang befindliche – internationale Phänomen des Informel bzw. des Abstrakten Expressionismus. Um 1959 beruhigen sich Novellis Bilder, die Gestualität und die Materialität verschwinden; Sprache dringt ein in Form von ganzen Sätzen, von Wörtern und Buchstaben. Das Geschriebene – es kann locker, aber auch dicht gedrängt erscheinen – ist nicht immer entzifferbar. Diese mehr oder weniger gestischen, meist lyrischen Bilder enthalten – als Vorboten des Kommenden – immer wieder Andeutungen auf Schriftliches/Gestisches. Der Schriftgestus dient zur Aussage dessen, was sich nicht in Worte fassen lässt. „Malen bedeutet auch, mit Zeichen auszudrücken, was man nicht über Handlungen ausdrücken kann oder vermag./ Das kann ein Grund zum weitermachen sein, auch wenn die Magazine der Welt voll mit Sachen zum anschauen sind,“ schreibt Novelli 1962/63.

Die Phase zwischen den informellen Werken und denjenigen, die im Zeichen der Universums-Darstellung liegen, sind von einer ganz besonderen Form der Übermalung gekennzeichnet. Von Novelli selbst Gemaltes wird mit Schleiern weißer Farbe in verschiedener Dichte überzogen, sodass nur mehr Teile der unterliegenden Malerei erkennbar sind. Dazu folgendes Zitat aus dem „Uomo cyote“: „Weiß ist ganz wichtig (einen Körper verdecken, eine Stadt, eine weiße Welt und kleine bedeutungsträchtige Partien abkratzen, meist rot oder rosa); Weiß kann schroff sein, aufsaugend, weich aber undurchlässig, Weiß zwingt zu einer Lektüre der Oberfläche, taub wie geweißelter Sand, glitschig.“

V.

Die Tatsache, dass Novelli tagebuchartige Aufzeichnungen in seine Werke einbezieht, könnte auf den ersten Blick als Hinweis auf eine grundsätzlich subjektive, sehr persönliche Anlage dieses Werkes gedeutet werden. Tatsächlich hat Novelli aber seine Rolle als Künstler immer anders gesehen. Der Künstler, und damit er selbst, ist ein Vermittler zu einer Sphäre, die jenseits des pur Persönlichen oder Privaten liegt. Anfangs hat Novelli diese Sphäre im Sinne eines psychologisch Unbewussten gesehen, später mehr in einem gesellschaftlichen Sinn. Die Funktion der Kunst ist gesellschaftlich, sie soll Neues zeigen, sie soll verändern, ohne direkt politische Kunst im engeren Sinn zu sein.

„Die Leute verschließen die Augen vor den neuen Entwicklungen der Kunst, sie fürchten, dass ihre aus bequemen und angenehmen Vorstellungen über die Schönheit bestehende Welt zerbrechen könnte./ Das ist noch ein Grund zum Weitermachen, denn man erreicht so ein erstes Resultat, eine erste Funktion einer als ‚revolutionäre’ Untersuchung aufgefassten Kunst. Und zudem: je mehr Sprach- bzw. Zeichen-Universen erforscht und kommuniziert werden, desto breiter ist der den Betrachtern angebotene Bereich möglicher Erfahrungen./ Vor allem: Die Gesellschaftlichkeit einer Arbeit lässt sich nicht an ihrer allgemeinen Beliebtheit ablesen, sondern ergibt sich aus der Sozialität des Künstlers, dessen Existenz deckungsgleich wird mit der kontinuierlichen Übung seiner eigenen Sprache.“

Klar wird hier, dass Novelli keine rein ästhetische Auffassung von Kunst hat, Kunst ist nicht bequem, sie ist anstrengende Erforschung von Sprach- bzw. Zeichen-Universen, mit welchen der Künstler der vielgestaltigen Welt Herr zu werden versucht. Der Künstler sucht nicht nach individuellem Ausdruck, sondern nach einem Ausdruck des Gesellschaftlichen, dessen

Sprachrohr er ist. Das bedeutet übrigens nicht, dass eine solche Kunst nicht trotzdem originell bzw. individuell ist. Kunst zielt – indem sie mit den ästhetischen Traditionen und Konventionen bricht – auf eine Veränderung des Bewusstseins und damit schließlich der Verhältnisse.

(Copyright: Andreas Hapkemeyer/ Antonella Cattani contemporary art, Bolzano)